Rianne Wagner, Matt Ruark, Chris Clark, and Shawn P. Conley

Phosphorus Fertilizer Enhancement Products – What Do We Know?

With phosphorus (P) fertilizers being subject to sharp and volatile price increases over the past year, producers are seeking ways to cut their fertilizer costs without risking yield-limiting P deficiencies. While there’s no magical solution that will replace P fertilization and the 4Rs (Right Source, Right Rate, Right Time, and Right Place) of nutrient management, understanding the mechanisms of fertilizer enhancement products currently on the market can aid in the decision to use them.

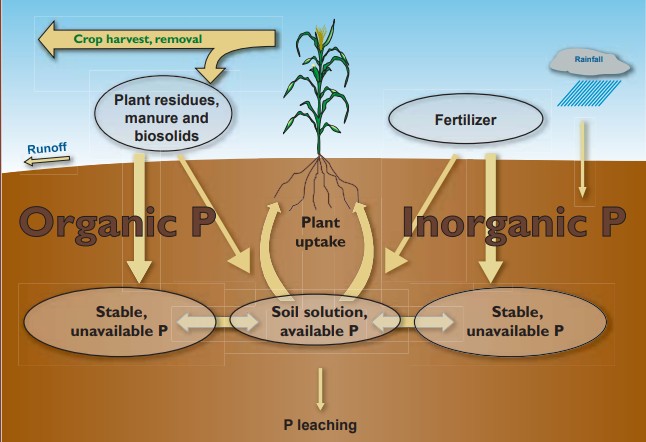

Soil contains large amounts of P in various forms (Figure 1), of which only soil solution phosphorus in the form of orthophosphate (H2PO4– or HPO4–) is available for plant uptake. There are two main processes in the soil that dictate P availability for plants: fixation and mineralization. Fixation is a general term used for the processes by which orthophosphate (soluble P) becomes unavailable to plants. Most P fertilizers (TSP, MAP, DAP) are highly soluble, immediately increasing the soluble P concentration in the soil upon application. However, this soluble P can quickly become “fixed” and bind to positively charged elements (cations) like aluminum or iron in acidic soil or calcium in neutral to alkaline soil. This process occurs due to the interaction of soluble P with cations in the soil solution or those on the surfaces of clay minerals. Once “fixed”, P is no longer plant available. P can be released from this “fixed” form through processes such as desorption and dissolution, but these processes occur slowly. P can also become plant available through the mineralization of P in organic matter, but once this P is plant available, it is also subject to the fixation and release processes described above.

Figure 1. The Phosphorus Cycle (Sturgul & Bundy, 2004).

Many P fertilizer enhancement products currently on the market promoted to improve the availability of P are designed to slow the release of P fertilizer into the soil (Slow Releasers), inhibit P fixation processes in the soil (Blockers), or promote the mineralization or release of P in the soil (Enzymes).

Slow Releasers

Slow-release P fertilizer enhancement products improve P use efficiency through limiting the fertilizer’s contact with reactive components of the soil. These products reduce the fertilizer’s surface area and contact time with the soil, decreasing the rate at which plant-available P becomes “fixed” into unavailable forms. By slowly releasing P throughout the course of the growing season, these products may better align P availability with crop demand.

A classic example of a slow releaser is coated MAP or DAP fertilizer. The coating reduces direct contact between the phosphate fertilizer and the soil, therefore minimizing P fixation and ensuring that the crop receives P throughout the growing season. Other products may rely on chemical binding with organic compounds to achieve the slow release of P.

Blockers

P fertilizer enhancement products categorized as “blockers” contain negatively charged compounds that attempt to limit P fixation reactions. Blockers contain negative charges that react with positively charged soil cations, allowing P from fertilizer to remain in the available soil solution pool. Blockers themselves do not contain any P, as they are meant to be combined with P fertilizer applications.

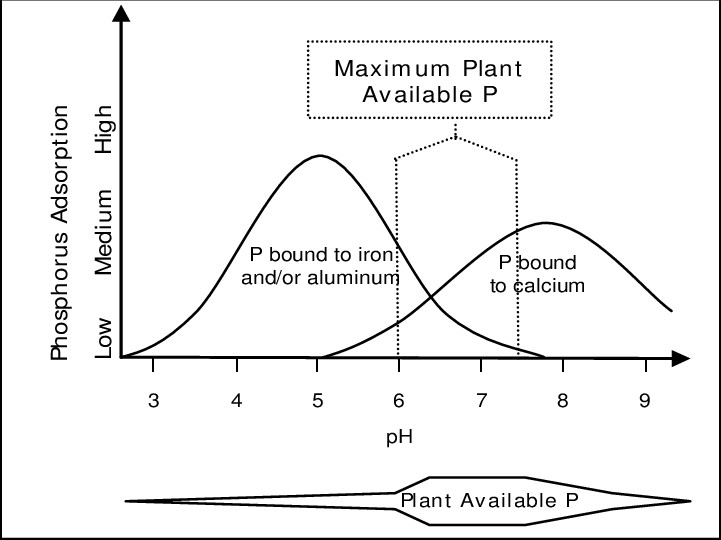

When considering the use of a blocker product, soil pH is an important condition to keep in mind. Under acidic soil conditions, Al3+ dominates exchange sites in the soil and aluminum- and iron- containing minerals dissolve more rapidly. In alkaline soil, Ca2+ makes up most of the exchange sites and concentrations of calcium and magnesium are elevated in the soil solution. These factors lead to increased P fixation (adsorption) in acidic or alkaline soils (Figure 2), decreasing soil solution P. When blockers are applied to soils with extreme pH, they prevent these cations from “fixing” available P, ensuring P remains available in the soil solution. However, in neutral pH soils, fixation reactions are less prominent, meaning that more P remains plant available. In soils where fixation reactions do not predominate, it’s unclear whether the use of a blocker product can reduce P fertilization rates.

Figure 2. The impact of soil pH on P availability (Hyland, 2004).

One of the most well-studied products in the blocker category is maleic-itaconic polymers. This product is either applied as a fertilizer coating or mixed with liquid formulations. The polymers react with chemical elements that precipitate or adsorb P in the soil, protecting P from undergoing these fixation processes and increasing available soil solution P. The maleic-itaconic polymer has been well studied but produces variable results. A meta-analysis by Hopkins et al. identified that the best-case use of this product was under low soil test P conditions and extreme pH (<5.7 or >7.7).

Enzymes

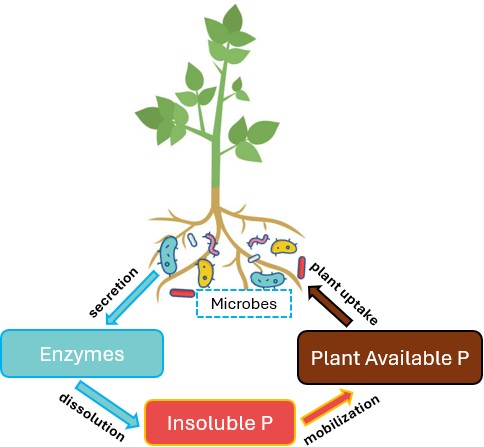

While both slow releasers and blockers attempt to reduce P fixation processes in the soil, enzymes focus on the process that transforms organic P to plant available P: mineralization. Mineralization is a biological process mediated by soil microorganisms and plant roots, which secrete enzymes that transform unavailable P into soluble P (Figure 3). P fertilizer enhancement products that fall under the enzyme category contain either microorganisms or the enzymes themselves that stimulate the mineralization process of the P cycle, supposedly leading to improved P efficiency and plant/microbe P acquisition. Achieving these results would require enzyme products to dominate the soil’s background biology and create conditions where mineralization increases above the standard rate. Extensive independent research has not been conducted on enzyme products, making it unclear whether these products are effective and under what conditions.

Figure 3. The mineralization process mediated by enzyme-secreting microbes.

The Bottom Line

Choosing the “best” P fertilizer enhancement product can seem like an overwhelming task, especially when profits are on the line. While these products may seem exciting and interesting, especially as more of them come onto the market every year, sufficient field trials to evaluate the probability of product success are limited. Of all the products currently available, maleic-itaconic polymers have been studied the most extensively and have the best evidence for success when extremes in soil pH are present. Overall, more independent, field-based studies are needed to evaluate the likelihood of these products resulting in yield increases or a reduction in P fertilizer application.

Before considering the use of a P fertilizer enhancement product, it is advised that producers manage pH in the optimum range, build and maintain soil test P in the optimum soil test range, and apply P at removal rates. Incorporating these management practices is recommended to minimize P-related yield drags on soils in Wisconsin. While there is only a 44% chance of a yield increase when P fertilizer is applied to soils testing in the optimum range, Wisconsin-based research suggests that soils testing in the optimum range are more likely to lead to greater yields than soils testing below optimum. It’s important to remember that fertilizer enhancement products are meant to supplement, not replace, sound management practices such as the “build and maintain” approach. A strong nutrient management plan based on the 4Rs remains the best strategy for long-term fertilization success.

Sources:

Hopkins, B. G., Fernelius, K. J., Hansen, N. C., & Eggett, D. L. (2018). AVAIL Phosphorus Fertilizer Enhancer: Meta-Analysis of 503 Field Evaluations. Agronomy Journal, 110(1), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2017.07.0385

Hyland, C. (2005). Phosphorus Basics—The Phosphorus Cycle. Cornell University Cooperative Extension. http://nmsp.cals.cornell.edu/publications/factsheets/factsheet12.pdf

Sturgul, S., & Bundy, L. (2004, March). Understanding Soil Phosphorus. Nutrient and Pest Management Program. https://ipcm.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/54/2022/11/UnderstandingSoilP04.pdf

Weeks Jr., J. J., & Hettiarachchi, G. M. (2019). A Review of the Latest in Phosphorus Fertilizer Technology: Possibilities and Pragmatism. Journal of Environmental Quality, 48(5), 1300–1313. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2019.02.0067