“We believe this work should be supported through industry funding rather than this program.”

If you work in applied weed science, you have probably heard this line. I certainly have.

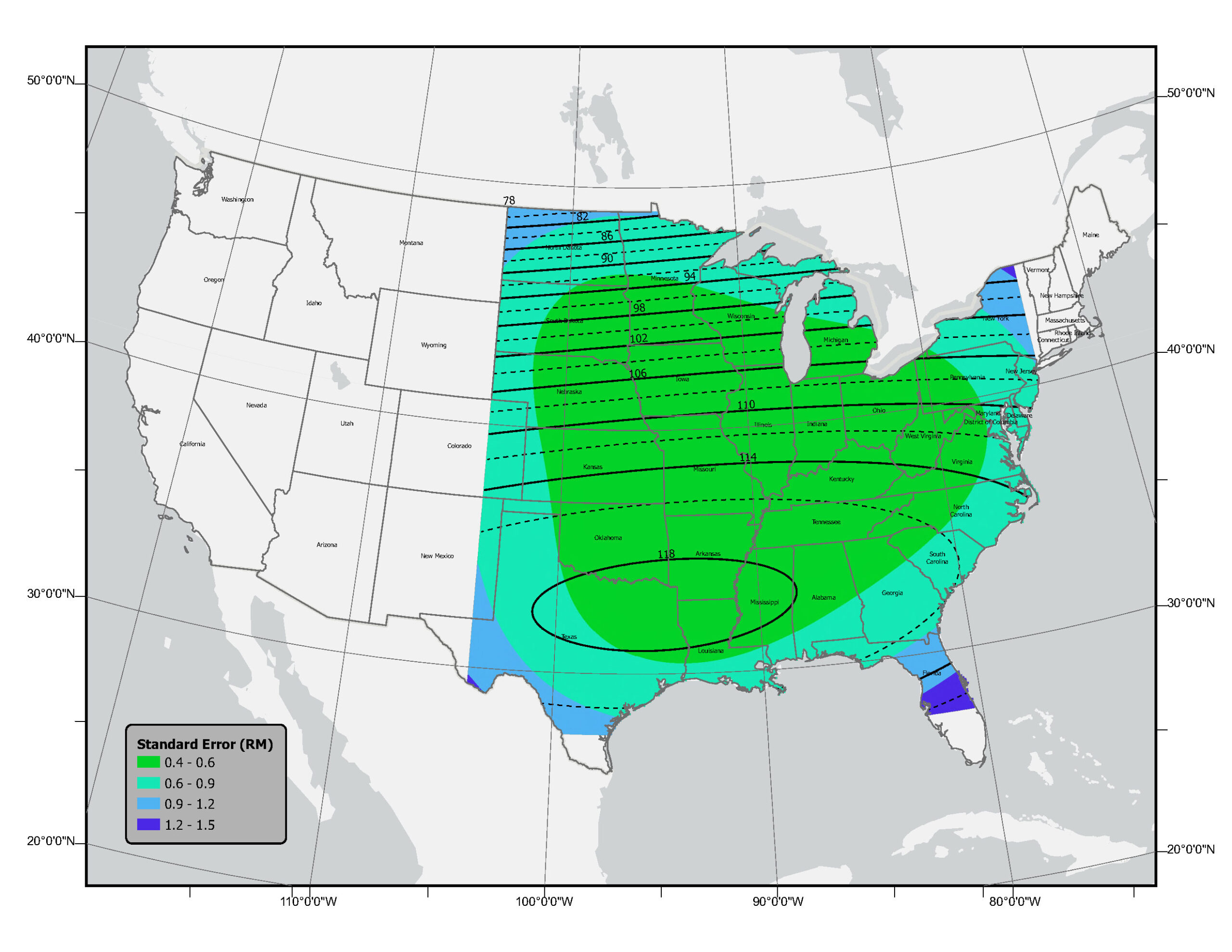

I am a university faculty member with nearly ten years of experience in applied research and extension, focusing on herbicide-resistant weed management in corn and soybean systems. Multiple-herbicide resistance is spreading rapidly across the U.S. and beyond, making weed management increasingly expensive, complex, and unpredictable for growers. What some call “spray and pray” research is, in reality, systems-level science with enormous grower and public benefit. In 2025 alone, corn and soybean covered nearly 180 million U.S. acres, with herbicides applied on more than 95 percent of that land. The scale and relevance of this work could not be clearer.

Yet almost every forward-looking, integrative grant proposal my lab and colleagues submit is rejected with the same four words: “Industry should fund this.” This response comes even when proposals integrate chemical weed control with cultural or mechanical strategies. On the surface, it may sound reasonable, but the result is repeated stalling of strong ideas. Startups often cannot afford multi-site, replicated testing. Large crop protection companies understandably prioritize projects tied to their pipelines, and equipment companies typically don’t fund independent, third-party applied agronomic research. Concepts without a commercial champion, such as cultural strategies for weed management, struggle even more.

Industry and commodity boards are essential partners, and I am deeply grateful for their support. They provide more than 80 percent of the funding for our WiscWeeds program, and their contributions are vital to the success of applied research. Yet their resources are finite, and it is unrealistic to expect them to fund all research needed to meet grower and societal priorities. Commodity prices, tight budgets, and cost pressures across agriculture only widen this gap.

Recent unfunded proposals illustrate what is lost under this mindset. This year alone, we submitted projects to:

- Integrate cover crops, narrow-row early-planted soybeans, and soil-residual herbicides to reduce post-emergence sprays.

- Validate targeted herbicide application systems (aka see-and-spray) to manage late-season escapes and reduce weed seedbanks.

- Use spatial spraying maps to guide variable-rate preemergence herbicide programs and cover crop seeding.

Each project had strong preliminary data and enthusiastic grower interest, yet all were rejected with the same rationale: “Industry should fund this.” These are not speculative ideas, they are practical, scalable, and grower-driven solutions that cross traditional disciplinary boundaries.

Applied weed and herbicide resistance management is far from solved. While industry contributions are vital and deeply appreciated, long-term solutions also require unbiased, independent development and testing. Without broader public investment, some of the most promising innovations will remain stalled.

After a decade of repeated rejection, I ask myself: what am I failing to convey? The frustration is not in being told “no”, rejection is part of research, but in hearing over and over that ideas aimed at improving agricultural sustainability, reducing herbicide reliance, and testing novel integrated approaches simply don’t fit anywhere unless industry decides they are valuable. My team continues to refine and resubmit proposals, yet the structural disconnect persists. Projects that directly address grower needs, protect public resources, and strengthen agriculture are often overlooked because they do not align neatly with commercial incentives. This dynamic limits innovation, narrows the pipeline of new weed management strategies, and slows progress at a time when we need more practical tools to confront herbicide resistance and environmental challenges.

My goal here is to communicate this situation publicly, show that we are actively trying, seek advice on how to better convey the need for broader support, and explore ways to bridge the structural barriers slowing progress. Another ten years of “let industry fund it” is a luxury agriculture cannot afford IMO. Long-term solutions require a collaborative approach where public investment, industry support, grower participation, and academic expertise work together to keep practical, independent research and innovation moving forward.

These are my two cents for today.

Written by Rodrigo Werle, Associate Professor and Extension Cropping Systems Weed Scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and proud PI of the #WiscWeeds lab. Contact Rodrigo at rwerle@wisc.edu.